-40%

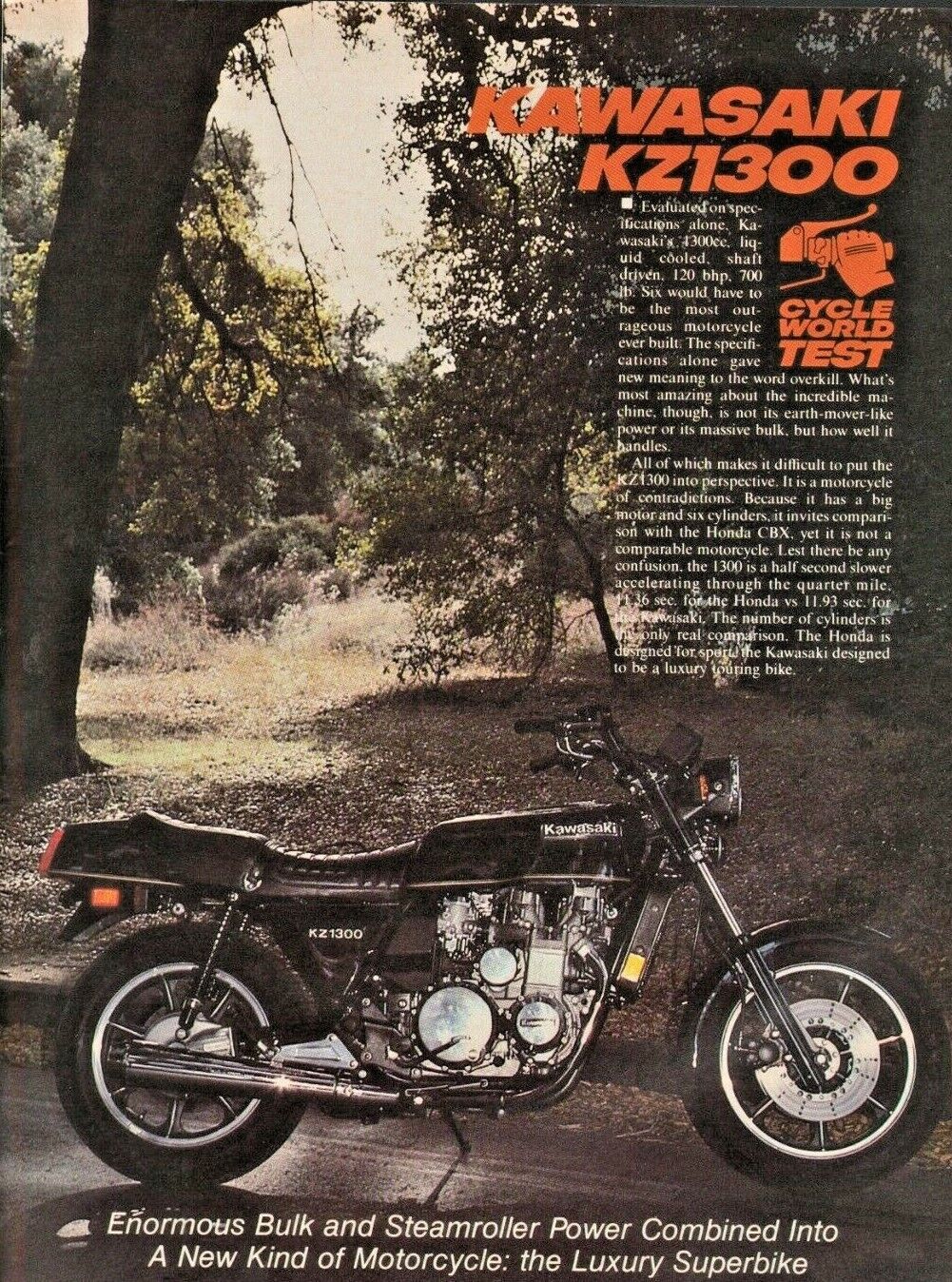

1979 Kawasaki KZ1300 - 8-Page Vintage Motorcycle Road Test Article

$ 7.37

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

1979 Kawasaki KZ1300 - 8-Page Vintage Motorcycle Road Test ArticleOriginal, vintage magazine article

Page Size: Approx. 8" x 11" (21 cm x 28 cm) each page

Condition: Good

...

There are comparisons to be made, but

not with the CBX. Instead, the 1300 could

be compared to the Honda Gold Wing or

Yamaha’s XS Eleven, both big, refined,

heavy touring bikes made for long dis-

tances on open roads with big loads.

The Kawasaki is that kind of bike. Only

better.

Beginning in June, 1973, Kawasaki en-

gineers began work on Model 203. which

was to become a luxury high performance

motorcycle. Various engine configurations

were initially considered but the motorcy-

cle was to have 1200cc and a shaft drive.

The original 900cc Z1 had been intro-

duced the year before and the sport market

was considered well covered.

Six cylinders was considered the max-

imum number for the engine size and had

an undeniable market appeal. At that

time, the Benelli Sei hadn’t been intro-

duced and the only Honda with six cylin-

ders had been a GP racer made in a

previous decade. While a V-Six. like the

Laverda endurance racer, could be more

compact, Kawasaki had more experience

with inline engines and could design an

inline Six sufficiently compact to fit a

motorcycle.

That's where the liquid cooling comes

in. Although an inline Six. with cylinders

lined up across the frame, could be air

cooled adequately, liquid cooling could

make the engine more compact because

less room is needed between cylinders.

Liquid cooling, of course, also has merit

for touring bike use: it insulates against

mechanical noise, making the bike qui-

eter; it increases longevity through precise

control of operating temperature; and it

allows more efficient running by holding

temperatures constant and higher under

normal operation than is possible with an

air cooled engine.

Because the Six was to be a touring bike

instead of an all-out sport bike, the design

is compromised more toward touring than

sport in a number of ways. Because ulti-

mate power potential wasn't needed, the

engine is decidedly undersquare with a

62mm bore and 71mm stroke. An over-

square engine has more piston area, more

room for valves and lower piston speeds,

all of which contribute to higher horse-

power, but the undersquare engine is nar-

rower and, all other things being equal,

produces more low-end and mid-range

power. Just the ticket for a louring bike.

Most of the design innovations narrow

the engine across the cylinders and head,

rather than at the crankshaft. While

Honda moved the alternator and ignition

behind the crankshaft to keep the bottom

of the CBX Six narrow for improved cor-

nering clearance, Kawasaki left the alter-

nator on the right end of the crankshaft

and mounted a torsion damper/flywheel

on the left end of the 1300’s crankshaft.

The weights help balance the Sixes’ cycli-

cal vibrations but don’t help cornering

clearance.

To keep the crankshaft short, there’s

only one drive chain, a 32mm Hy0Vo.

which drives a jackshaft directly behind

the crankshaft. There is no cam chain from

the crankshaft. Instead, a 10mm Hy-Vo

chain runs from the jackshaft to drive both

cams.

The incredible sophistication of the

1300 is apparent in the drive system. Once

power is transmitted to the jackshaft, it

goes in two directions. To the right side, the

power flows through a spring-loaded cam-

type damper to the 40mm Hy-Vo chain

which drives the mammoth clutch.

To keep the jackshaft narrow, the

damper drives an inner shaft which is

splined to the outer shaft which drives the

clutch drive chain. On the left side of the

primary drive chain is. first, the cam chain,

then a bearing, then a roller chain which

drives an auxiliary shaft, and finally a

nylon spur gear which drives the oil pump.

The roller chain is the only one of that type

in the engine.

The auxiliary shaft, which runs directly

above the jackshaft behind the cylinders, is

just as busy. It is driven at its left end and

drives the pulse generator of the transistor-

controlled breakerless ignition through a

nylon spur gear on its right end. In the

middle of the auxiliary shaft is a bevel gear

which drives a tiny shaft running forward

between the center pair of cylinders and

which has the waterpump mounted on its

forward end.

To keep the auxiliary shaft drive chain

and the cam chains taut, there are spring

loaded, ramp-type automatic cam chain

tensioners on both chains. There is also a

cover plate on the left-hand side of the

auxiliary shaft housing which can be re-

moved. allowing the drive chain to be

disconnected so that the cylinders can be

removed.

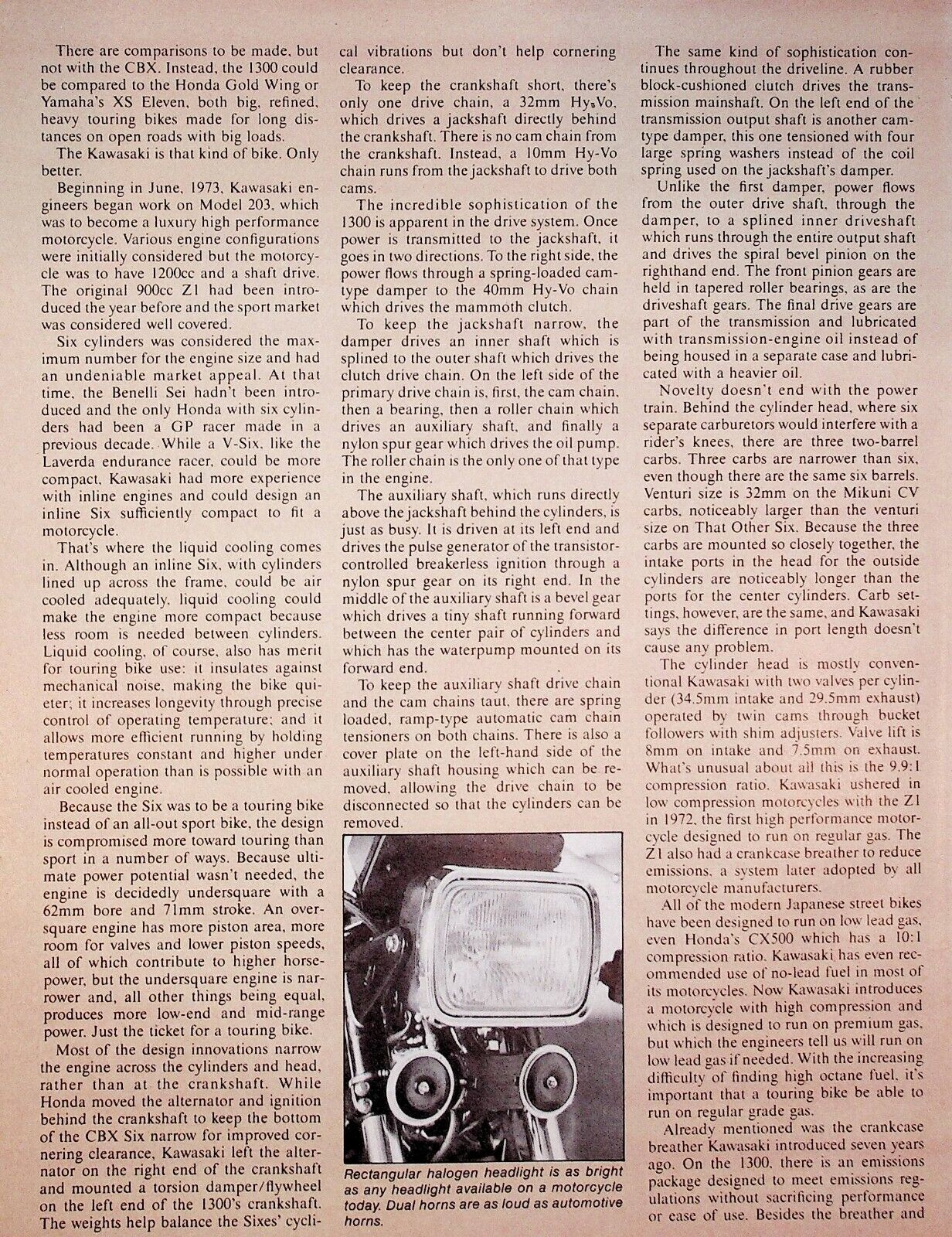

Rectangular halogen headlight is as bright

as any headlight available on a motorcycle

today. Dual horns are as loud as automotive

horns.

The same kind of sophistication con-

tinues throughout the driveline. A rubber

block-cushioned clutch drives the trans-

mission mainshaft. On the left end of the

transmission output shaft is another cam-

type damper, this one tensioned with four

large spring washers instead of the coil

spring used on the jackshaft's damper.

Unlike the first damper, power flows

from the outer drive shaft, through the

damper, to a splined inner driveshaft

which runs through the entire output shaft

and drives the spiral bevel pinion on the

righthand end. The front pinion gears are

held in tapered roller bearings, as are the

driveshaft gears. The final drive gears are

part of the transmission and lubricated

with transmission-engine oil instead of

being housed in a separate case and lubri-

cated with a heavier oil.

Novelty doesn't end with the power

train. Behind the cylinder head, where six

separate carburetors would interfere with a

rider’s knees, there are three two-barrel

carbs. Three carbs are narrower than six,

even though there are the same six barrels.

Venturi size is 32mm on the Mikuni CV

carbs, noticeably larger than the venturi

size on That Other Six. Because the three

carbs are mounted so closely together, the

intake ports in the head for the outside

cylinders are noticeably longer than the

ports for the center cylinders. Carb set-

tings, however, are the same, and Kawasaki

says the difference in port length doesn't

cause any problem.

The cylinder head is mostly conven-

tional Kawasaki with two valves per cylin-

der (34.5mm intake and 29.5mm exhaust)

operated by twin cams through bucket

followers with shim adjusters. Valve lift is

8mm on intake and 7.5mm on exhaust.

What's unusual about all this is the 9.9:1

compression ratio. Kawasaki ushered in

low compression motorcycles with the Z1

in 1972. the first high performance motor-

cycle designed to run on regular gas. The

Zl also had a crankcase breather to reduce

emissions, a system later adopted by all

m o t o rcycl e m a n u fa c t u re rs.

All of the modern Japanese street bikes

have been designed to run on low lead gas,

even Honda's CX500 which has a 10:1

compression ratio. Kawasaki has even rec-

ommended use of no-lead fuel in most of

its motorcycles. Now Kawasaki introduces

a motorcycle with high compression and

which is designed to run on premium gas.

bin which the engineers tell us will run on

low lead gas if needed. With the increasing

difficulty of finding high octane fuel, it's

important that a touring bike be able to

run on regular grade gas.

Already mentioned was the crankcase

breather Kawasaki introduced seven years

ago. On the 1300. there is an emissions

package designed to meet emissions reg-

ulations without sacrificing performance

or ease of use. Besides the breather and...

13979-AL-7904-08